October 17, 2018

By Timothy Bowles, Joanna Ory, and Alastair Iles

(From left to right) Timothy Bowles is an Assistant Professor, Joanna Ory is a Postdoctoral Fellow, and Alastair Iles is an Associate Professor, all with the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management.

Do you have an intuitive sense of what it means to be healthy, and how to stay healthy? You probably do, even if it’s hard to put into words. Being healthy is more than being free from disease; it is about the ability to live a full life and to bounce back after challenging times. Our health reflects who our parents are, the environment we live in, how we take care of ourselves, and how all of these interact. If heart disease runs in the family, then we might have to make an extra effort to eat well and exercise, but our work will be undermined by being in a stressful environment.

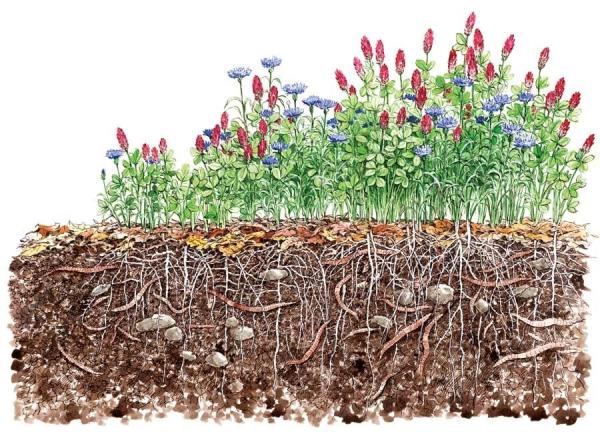

Roots, earthworms, organic matter, and microbes make healthy soils. Photo by Alameda Backyard Growers.

Like us, soil is living and breathing. It is the habitat for a tremendous diversity of organisms, most of which we cannot see without the help of a microscope or other scientific tools. By focusing on whether soil is healthy, we are putting this life at the center of attention. A healthy soil functions as a whole ecosystem in itself, and provides an array of benefits that we rely on—like helping to retain, cycle and cleanse water; recycle nutrients; mitigating climate change; and growing food, fibers, and fuel. Soil, too, has parents (rocks), takes a long time to grow, and lives in particular environments (e.g. valleys). No matter where soil is found, all soils require careful management to be productive and enduring long into the future. For example, sandy soil on a slope is more vulnerable to erosion, compared to clay soil on flat ground, calling for special care.

“Healthy soil is the ability of the soil to feed the microbes which in turn nourish the soil. When microbes in the soil are healthy, it results in more productive plant growth, less need for pesticides and more resiliency to erosion and flooding.” ~Survey respondent

Unfortunately, modern, input-intensive agriculture often undermines the health of soil. It can do so by depleting the organic matter needed to sustain soil life, reducing the abundance and diversity of organisms in soil, and increasing erosion of irreplaceable topsoil. Together, this damages the very resource base on which agriculture depends. Managing for soil health means supporting abundant, diverse soil life, whereas industrial agriculture focuses mainly on the crop. In practical terms, this means feeding the life with living roots in the soil, such as with cover crops, and with compost or manure. It means limiting the disruption of soil life’s habitat by reducing tillage. And it calls for maximizing the diversity of plants and animals, such as through crop rotation, intercropping, or integrated crop-livestock systems. Yet there can be many barriers—technical, socioeconomic, policy—to farmers making changes in their practices to improve soil health, even if they want to.

Showy crimson clover flowers stand above other mowable clovers in a mix suitable for almond orchards. Photo by: California Agriculture, University of California ©2018 The Regents of the University of California.

Despite benefits such as improvements in crop quality and yields, water savings, favorable economic outcomes for farmers, and greater climate resilience, the majority of farmers in California have not adopted these practices. For example, only 5 percent of growers on the Central Coast use cover cropping (or planting a crop like hairy vetch instead of letting a field be fallow) to provide fertility, reduce soil erosion, and hold moisture. Since fall 2017, the Berkeley Food Institute has been running a project to study these barriers, with an eye to helping develop new policies to nourish our soils in California. We are working to identify what will motivate California farmers and ranchers to use soil building practices, and what is impeding them from doing so.

Our first step was to conduct a statewide survey this past summer of agricultural advisors and extension staff who work with growers and ranchers, and who may recommend specific soil health practices. Some 140 responses have helped us gain a better understanding of how extension agents think about soil health, the conditions under which they will advise growers to use soil practices, and what barriers they regard as particularly important. The five most important practices for building soil health according to the agents are cover cropping, rotational grazing, reduced tillage, diverse crop rotations, and riparian herbaceous cover. Very interestingly, many extension staff put water at the center of soil health: in a state that is facing long-lasting drought and climate change, healthy soils can hold water for longer. This can make better use of irrigation and any rainwater.

“[Healthy soil is] soil that you wouldn’t mind a newborn baby to crawl around in, and you feel safe if you ate some of (it).”

~Survey respondent

Dr. Joanna Ory, postdoc in the project, presents on soil health. Photo by: Organic Farming Research Foundation.

Extension staff view uncertain or low return on investment as the strongest single barrier to the use of soil health building practices among farmers and ranchers. The costs of adoption and maintenance, labor needs, and concerns with food safety are seen as other major barriers. For example, some agents commented that installing hedgerows might not be worthwhile for growers due to high long-term maintenance requirements and lack of obvious financial benefit for the grower. In cases like this, it seems financial incentives and promoting environmental stewardship may be important in encouraging greater use of soil health practices.

For growers who do use these soil-building practices, what motivates them? Many extension staff said that economic opportunities related to long-term investment in soil health, water savings, environmental values and access to demonstrations and successful neighbors were major motivating factors. For example, one survey respondent wrote, “If a practice is economically viable and improves the overall yield, profit, soil health, or crop quality, most farmers are motivated and excited to apply that practice to their farms.”

Our next steps are to conduct farmer interviews and to develop recommendations for extension services and the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Healthy Soils Program.

For more on healthy soils, please visit the Natural Resources Conservation Service.