By Rachel Maas and Caroline Hart

In fall 2019 students in the Graduate Certificate in Food Systems core course “Transforming Food Systems: From Agroecology to Population Health” visited community organizations in the East Bay. The following reflections are a sample of how these visits changed students’ understanding of food systems.

Rachel Maas is a masters student at the School of Public Health.

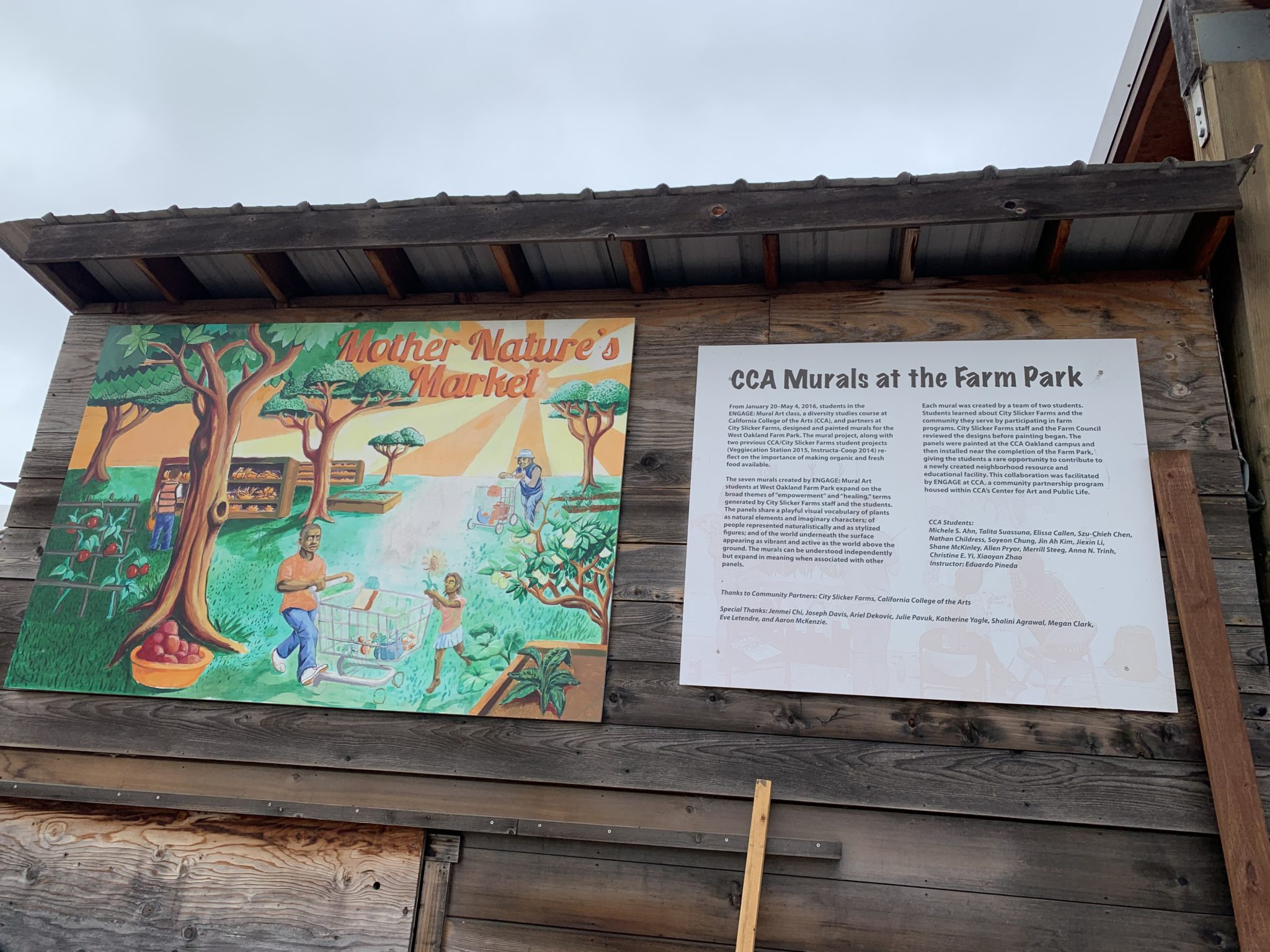

Photo by Rachel Maas.

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to visit City Slicker Farms (CSF) at their Farm Park in West Oakland. City Slickers Farm is a food justice organization that has helped bring fresh, local produce to Oakland residents— especially low-income minority communities—for nearly twenty years through establishing urban community gardens and providing farm education. Central to CSF’s mission is to (literally) put down roots in the face of growing displacement and gentrification.[1] When I arrived, the modern, open-layout park immediately signaled the staying power of this East Bay urban agriculture organization. I walked in the open iron gates and under the large welcome sign onto a concrete slabbed area outfitted with a pavilion, picnic tables, and an outdoor kitchen. To the left in the distance I could hear children on the park’s playground, to my right were a group of high school students giggling and playing a sort of eeny-meeny-miny-moe with their assigned tasks. I made my way to the tool shed and asked another volunteer with a wheelbarrow where I could report for volunteer duties. I was kindly led to the chicken area, where I met Farm Park Manager Eric Telmer. He introduced me to two community volunteers and told me our group task: turning the latest batch of compost. But before digging into the fresh compost, a regular City Slicker volunteer gave me the grand tour.

Photo by Rachel Maas.

The West Oakland Farm Park features twenty chickens and one very cute Chance the Rabbit. There’s a central walkway that spans the length of the farm, from chicken coop to playground. On one side are CSF’s produce beds, from which the community can purchase fresh produce on a sliding scale. To the opposite side are community plots, as well as a few new beds of soil set aside for a new project with a local school. Near the chicken coop are two small equipment sheds, a small orchard of stone fruit trees, and a farm office and touchdown space. Just off the pavilion is a tent where community members can start their crops from seed before transferring the sprouts to their plots. As we walked passed the pavilion I asked my volunteer tour guide how long ago CSF started. She pointed to a tenth anniversary flyer proudly displayed along a row of promotional posters from years past—“since 2001,” she calculated. After my tour we made our way back to the compost, where I helped Eric assemble a chicken wire compost bin and then began shoveling the batch of compost from its old bin to the new. I learned that this movement was critical to developing uniform compost, and that the steamy center of the compost we were transferring was the hottest part—around 160 degrees, according to Eric. This compost was only around a week old and composed of mostly chicken manure, spoilt chicken feed, and produce scraps. Most of the compost would remain at the Farm Park, but some would be transported to offsite gardens within the CSF network. “None of this goes to waste,” Eric assured me. After finishing the compost turning and weeding some of the largest dandelions I’d ever seen, Eric sent me to harvest a bed of butternut squash. The farm was winding down for the day, most of the student volunteers had left, and Eric was greeting a couple of city officials for an end-of-day meeting. As I clipped squash stems, I chatted with one of the remaining students. He’s completing his senior community service project at the farm, spending a few hours assisting Eric each week. With all the beautiful squash in a wheelbarrow, I carted my harvest back to the shed and tidied up before thanking Eric for letting me help and bidding Chance the Rabbit adieu.

Photo by Rachel Maas.

My afternoon at City Slicker Farms provided new knowledge of composting, and of how a local urban farm functions. There’s a sort of symbiotic relationship between CSF and local students—CSF relies heavily on student volunteers at the Farm Park, and students receive a rich urban farming education in return. But my visit also affirmed for me some of the ideas that we’ve returned to throughout the semester. CSF is using simple, tried-and-true methods to promote food justice: rehabbing urban plots into farmable land, building a network of small gardens and schools, educating and empowering community members to grow food, and selling produce to locals accessible prices. There’s no expansive acreage, no sophisticated machinery, no industrial fertilizer or pesticides. Like many of the farmers we’ve heard from this semester, Eric and the rest of the team rely on extensive knowledge of regenerative agriculture techniques and environmental stewardship. This work is painstaking and slow. While CSF now has a comfortable homebase on Peralta Street, the organization was changing the East Bay food system for over a decade before it secured a grant that enabled CSF to purchase its own land. The Farm Park didn’t open until 2015. CSF spent that first fourteen years frequently moving spaces and focusing efforts on establishing small gardens throughout town. This to me is a powerful reminder of the immense privileges that comes with land ownership—especially in a city like Oakland—and the resilience and flexibility required to pave change without those privileges. But I think that the modest roots of CSF are critical to its staying power: it was built from a network of community members, long before the farm had its own physical space. Oakland residents are the beating heart and center, and I can’t imagine a successful food sovereignty movement starting any other way.

[1] City Slicker Farms. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2019, from http://www.cityslickerfarms.org/index.php

Caroline Hart is a masters student at the Graduate School of Journalism.

I visited Café Ohlone by mak-‘amham for their Tuesday evening tea. The cafe is situated in the back patio of University Press Books and Musical Offering Cafe—the heart of downtown Berkeley, where the cafe stands apart from numerous other offerings as the only native food institution. The tea functions as an educational event, celebration and small meal for the public at a cost of $20. To begin the event, founder and Ohlone Tribe Member Vincent Medina started with a prayer in his native language, and said that he hopes that sharing his language, food and philosophy for just a few hours can provide a meaningful avenue for dialogue, thought and decolonization.

This visit affirmed my belief that most food is deeply colonized, and that issues of land ownership and agroecology are difficult to disentangle from food in America.

The cafe, in its concept and in its practice, is acutely intentional. From the foraged nuts, serving as decorations on each table, to the structure of the event—opening with a prayer and explanation of the food, then inviting elders to come take food first, followed by eating and drinking at long, communal tables—Café Ohlone serves as an institutional example of intentional change within the food system. Medina’s articulated goal, which he stated is “decolonization in action” through these meals, is necessary for its blunt integration of sociocultural and economic perspectives.

Another food systems concept at the core of the cafe is race, diversity, and inclusion in agriculture. In this case, the cafe prompted me to think about the scale and scope of agriculture in colonization, and where foraging falls within systems of agriculture. In Medina’s discussion of foraged ingredients which he used in the meal, he touched upon his tribe’s tradition of foraging on what used to be Ohlone land, which eventually turned over to Spanish, then American colonial hands.

The evening tea also touched upon agroecology in that the presentation related practices of small-scale food production and sustainability, through feeding the Ohlone community and through foraging. Medina spoke at length about the nature of land ownership, and what it means for Ohlone people to have survived and persisted in the face of colonization.

As Medina spoke of the ingredients in the chia porridge and acorn flour brownies, he catalogued each nutritional benefit. From Omega 3 fatty acids in chia seeds to the low glycemic index of agave syrup, he said that the food his cafe and community makes needs to be as nutritionally dense as possible. Why? He aims to counteract, in any way he can, the chronic health issues his community battles, such as high blood pressure and hypertension. In this way, he intends for the food to nourish, and acknowledged the role food has as medicine.

Intertwined in his discussion of food as medicine was his discussion of food as a cultural object, which is subject to cultural norms. While the cafe uses ingredients he described as traditional, such as acorn, they also cook with modern ingredients, such as chocolate.

In an earnest anecdote, Medina spoke about how, in his formulation of the brownie recipe, he spoke with elders about a desire to initially bake with acorn flour, hazelnut flour, and chocolate, and eventually scale back to the most pure and authentic baked good, made solely with acorn, after some time. The elders protested: “Keep the chocolate. We love chocolate!” Through this, Medina spoke of remaining authentic to not only tradition and traditional ingredients, but also to peoples’ evolving tastes, within the period of time and the location. This made me think about the issue with golden rice—which researchers heralded as the next great solution to hunger, without fully considering what food means beyond providing nutrients, and what local people ate where they wanted to push the crop. In considering solutions to hunger, it’s actually quite disrespectful to assume what people want to eat without asking them and without contemplating why it matters to them. It also matters who is speaking to whom in cases of suggestion about something as personal and as complicated as food.

In terms of what I’d like to share with others, I’d definitely note that this kind of accessible, local education seems necessary within the food system! Beyond educating people about native food and culture within the Bay Area, I wonder what other aspects of food culture need attention and representation. In my role as a journalist and documentary filmmaker, I am excited to look for these stories and think critically about what aspects of food culture are represented in the media.