September 18, 2019

September 18, 2019

By Kristine Madsen

Dr. Kristine Madsen is an Associate Professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health and serves as Faculty Director for the Berkeley Food Institute.

Our food system is driving one of the most pressing problems we confront in the 21st century: diet-related disease. As a recent Op-Ed in the New York Times states: our food is killing us—over 2,300 people die from diet-related disease every day—and a report released last week documents an historic level of obesity in the United States.

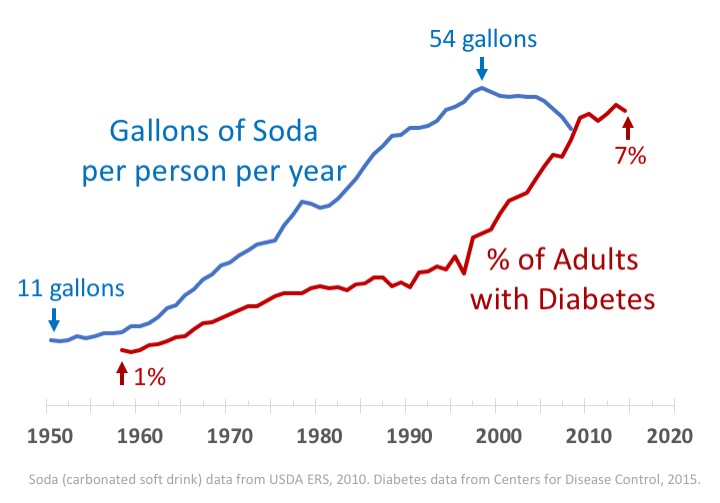

Figure 1: Trends in soda consumption and diabetes in the U.S.

What is it in our diet that is leading to these levels of disease and death? Added sugars are a proven driver of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. Figure 1 shows a dramatic increase in soda consumption in the U.S. since 1950, and the remarkably similar increase in diabetes that follows. Mounting evidence suggests that sugar is addictive, and we’ve shown that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) have addictive properties, especially in youth.

Retail prices of sugar and soda have dropped over the last 3 decades (adjusted for inflation), while prices of healthy foods like fruits and vegetables have risen (Figure 2), as have societal costs. The economic burden of cardiovascular disease was over $300 billion in the United States in 2013, and is projected to top a staggering $1 trillion by 2030. The production of cheap food also carries environmental costs. Corn production in the U.S. (needed for the high-fructose corn syrup that sweetens soda) is heavily dependent on fossil fuel inputs and unsustainable land management practices, both of which lead to significant greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, corn uses more pesticides than any other crop, leading to other health risks and contamination of our air, soil, and water.

Figure 2: Trends in the price of foods (adjusted for inflation) in the U.S.

BFI is working on many approaches to transform our food system, and soda taxes are a critical tool to address diet-related disease. Our recent editorial in JAMA summarizes the state of the evidence on SSB taxes, which have 4 major goals.

First, soda taxes help to ensure that the price of SSBs accurately reflects their societal cost. All of the SSB taxes in the U.S. are excise taxes, which means they are paid directly to cities by SSB distributors, not consumers. Distributors pass the tax on to retailers, and the price of SSBs then increase, as we demonstrated in the first study published on Berkeley’s soda tax. Second, taxes generate revenues that cities can invest to create healthier communities. The $133 million in annual revenues from U.S. SSB taxes supports diverse programs, from prekindergarten care and education to improvements in parks to subsidizing fruit and vegetable purchases to diabetes prevention. Third, taxes reduce SSB purchasing and consumption. As discussed in our JAMA editorial, there is definitive evidence that purchases of SSBs drop as a result of SSB taxes. We also published the first study on the effects of SSB taxes in low-income neighborhoods, documenting a 52% decline in SSB consumption in low-income neighborhoods over the first 3 years of Berkeley’s tax. This is critical information because the burden of obesity, diabetes and heart disease is highest in low-income communities. Lastly, soda taxes are a powerful form of education for the public. Independent of changes in retail prices, the media surrounding taxes and the public passage of a tax influence consumers behaviours, as BFI affiliated faculty have shown.

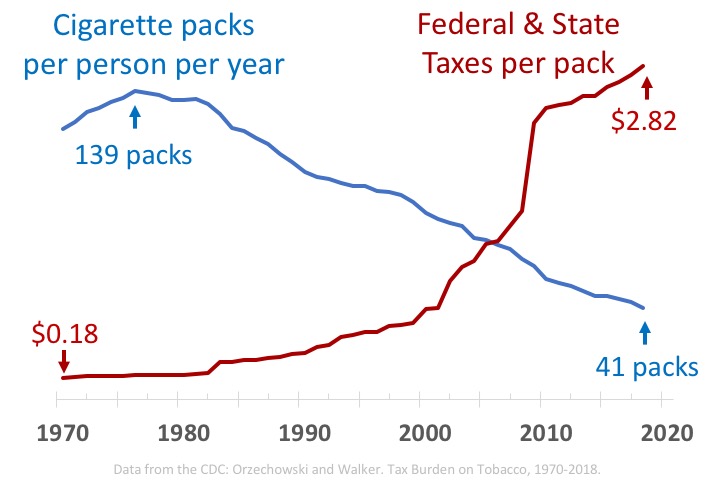

Figure 3: Trends in cigarette taxes and purchases

The success of SSB taxes to date echoes that of tobacco taxes. As tobacco taxes increased after 1970, cigarette purchases declined drastically. However, efforts to reduce smoking went beyond taxes; they included creating “no-smoking” workplaces and public spaces (like restaurants and bars, which the tobacco industry claimed would kill these still-thriving businesses), placing warning labels on cigarette packages, and banning advertising to children. The epidemic of diet-related disease in the U.S. requires similar multi-faceted efforts to educate the public and create an environment where healthy living is easier and more accessible to all.

BFI’s work in this area matters. As I wrote previously, the SSB industry’s trade group, the American Beverage Association, did an end-run around our democratic process in California in 2018, making it illegal to pass any local SSB taxes in California until 2030 and preventing us from replicating the success of anti-tobacco efforts (which relied heavily on federal, state, and local excise taxes). There are three avenues that can still be pursued to implement SSB taxes in California: repeal California’s pre-emption bill, and pass a statewide tax either via a ballot initiative or via legislation, like AB 138.

BFI is working to ensure that people have the facts and can make informed decisions about future potential SSB taxes. In partnership with the Praxis Project, we just conducted the first in a series of community briefings, in Fresno, with a wide-ranging group of stakeholders; additional briefings (the next is in East LA on October 29) will be posted in our calendar and social media. We continue our work studying the impacts of SSB taxes in low-income communities (we are now analyzing data from San Francisco and Oakland as well as Berkeley) and have a $4 million NIH-funded collaboration with Stanford and UCSF to study the impact of healthy workplace initiatives and fruit and vegetable vouchers in addition to SSB taxes. This work to ensure healthier diets– one aspect of BFI’s effort to transform the food system– could not happen without your support. Your gifts allow us to broaden the impact of this research, and wherever you live, your citizen engagement on these issues will be essential to ensure that the health and well-being of our communities remain a top priority for lawmakers.