Q&A

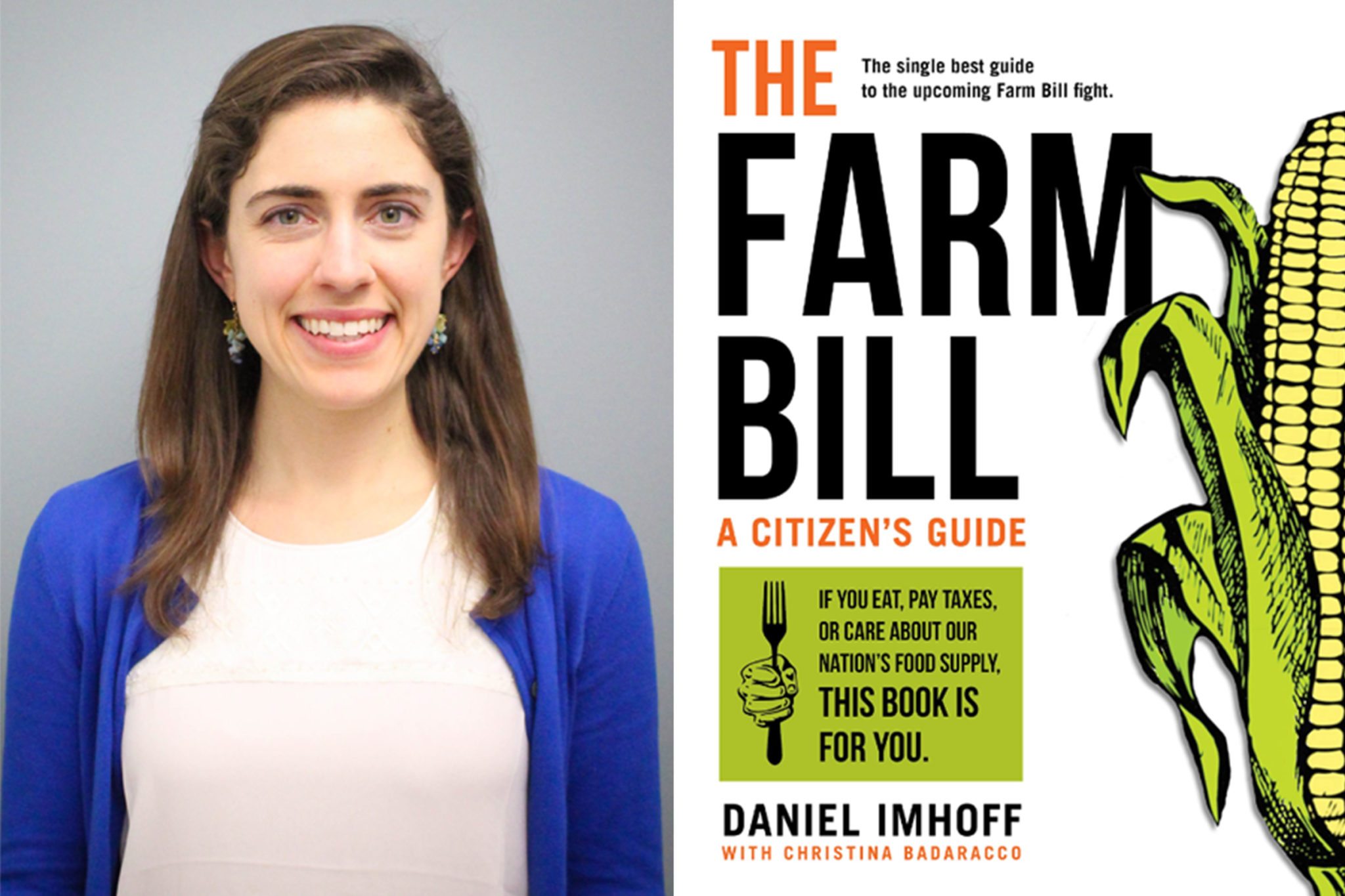

Christina Badaracco: Advocating for a Citizen’s Farm Bill

The dietitian and Berkeley Public Health alum views the Farm Bill as a potential avenue to improving access to healthy and sustainable food.

In January 2019, just a month after the most recent Farm Bill was passed by Congress and signed into law, Daniel Imhoff and Christina Badaracco published The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide. The book, which includes graphics, sidebars, expert essays, and breakdowns of key policy issues, serves as a primer to the Farm Bill and its implications for farmers, farmworkers, and everyday Americans. Where the Farm Bill itself can be a behemoth of inaccessible legal text, The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide makes the information approachable to the people the bill impacts.

Though much has changed since 2018 — the pandemic has disrupted the food supply chain, while climate change has led to more variable conditions for farmers and farmworkers — the book holds up as a crucial read for those wanting to learn about the Farm Bill, especially now on the precipice of another Farm Bill reauthorization.

To help write and edit the guide, author Daniel Imhoff conscripted UC Berkeley alum Christina Badaracco. Christina is a registered and licensed dietitian, and received her Master of Public Health degree from the UC Berkeley School of Public Health in 2017. She views the Farm Bill as key to improving access to healthy and sustainable food for all Americans. BFI sat down with Christina for her insights and expertise heading into 2023.

Researching and writing a book on the Farm Bill must have been a huge undertaking. What inspired you to take on this project?

It was an opportunity that came out of BFI, actually. In the spring of my final year of my MPH, Nina Ichikawa (BFI’s Executive Director) sent an email that author Dan Imhoff was looking for a graduate student to work with him on a book about the Farm Bill. I was very excited about that opportunity, and wanted to pursue it. First and foremost, I’m very interested in agricultural policies and sustainable agriculture. I also really enjoy writing, and it’s a real strength of mine. I thought it would be a good opportunity to learn more about the Farm Bill and the process of writing a book.

In the book, you and Imhoff discuss a discrepancy between healthy diets and the kind of crops that past Farm Bills have supported. How do you feel the Farm Bill fails when it comes to nutrition?

The 2018 Farm Bill does not increase access to healthy foods nor increase production of healthy foods, the same foods that we recommend Americans eat through dietary guidelines. That discrepancy happens through commodity subsidies and the crop insurance program. Support for crop insurance works for largely the major commodity crops, like corn, soy, wheat, and rice. Of these commodities, not all of them even end up in our food supply. Much of our corn is used for ethanol. The major commodity crops that do end up in the food supply predominantly end up in very heavily processed foods — the types of foods that we recommend Americans minimize consumption. These are the foods that are in packaged products with very long ingredient lists that are made cheap by the way that we subsidize their production through the Farm Bill.

Meanwhile, the foods that we recommend fill Americans plates get very, very little support through the Farm Bill and thus don’t have much of a chance to compete with subsidized commodities in the marketplace.

As a footnote, I was just listening to USDA Secretary Vilsack speak a few days ago, and he pointed out that there is some support in the Farm Bill for “specialty crops” like fruits, vegetables, and nuts. There’s a specialty crop block grant program in the Farm Bill, some support for organic farming conversion, and some support for whole farm revenue and insurance. So there are a few small ways in which diversified agriculture and specialty crops are supported through the Farm Bill. It’s not that they receive nothing. But it’s a very, very, very small slice of the pie.

The book refers to the healthcare community as “a sleeping giant” when it comes to interaction with the Farm Bill. From your perspective, as someone in the healthcare field, what are you hoping to see from the healthcare community during this upcoming Farm Bill year?

In the last few years, most of my work related to the Farm Bill has been focused on educating the healthcare community, in particular dietitians. But I would love to see more outreach to other types of healthcare providers, like physicians or nurses.

My own professional association, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, has been fairly involved with the Farm Bill. About six months ago I joined its Farm Bill Task Force. It’s a diverse set of dietitians from around the country, people of all ages and backgrounds. We are putting together recommendations, basically a position paper on what we are looking for in the 2023 Farm Bill. The Academy will then use that in its advocacy efforts over the next year leading up to the reauthorization. I would love to see other professional associations in the medical community, outside of dietetics, do something like that. They can put out thought leadership, both to their own groups of practitioners, but also to the public. In so many instances, people really look to the recommendations of physicians. If people see something written by a physician about what they should be eating or how much they should be exercising, that really adds a lot of weight to the recommendation. So I would love to see more public facing content around the Farm Bill from the physician perspective, especially.

In The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide, you and Imhoff outline a list of solutions you’d like to see in the next Farm Bill, such as supporting food crops that align with Dietary Guidelines and investing in ecologically-based farming. Are you hopeful that some of these recommendations might be implemented?

A main challenge in driving some of these solutions comes down to who is in Congress. I’ve been excited the last few years to see in the House and Senate agriculture committees more and more congressmen and women who are concerned about the way we produce and eat food. One example is Senator Cory Booker. I just heard him speak at the Milken Institute Future of Health Summit last December on the discrepancy between the way we subsidize food versus dietary recommendations and how we need to change the way Americans eat for better health outcomes. He discussed the enormous amount of money that we spend on healthcare when we eat such poor quality food. There are many other politicians on both sides of the aisle that are having important conversations. I’m excited that we have more and more folks in Congress who seem to be concerned and interested, and I am hoping that that translates into the Farm Bill drafts we will see this year.

The book ends with a call to action: “The time has come for a citizen’s Farm Bill.” What would a citizen’s Farm Bill look like to you?

Throughout the book, Dan and I wrote about the many different types of ways that people are affected by the Farm Bill in our roles as consumers, taxpayers, voters, farmworkers, or public health practitioners. With that in mind, we really need to change the way the Farm Bill is phrased. A citizen’s Farm Bill would look to minimize all of the negative externalities associated with food production in the United States and instead optimize policies and programs that promote food and nutrition security, livelihood and health, a robust agricultural workforce, and a healthy and affordable food supply for all Americans.