Q&A

Reversing the Trend of Black Land Loss

Attorney Dãnia Davy is informing Black farmers, policymakers, and the public on heirs property and its threats to land retention.

In 1967, twenty-two cooperative businesses across nine Southern states formed the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. The Federation was born out of both the Civil Rights Movement and the Black cooperative economy movement, in which Black-run farms and businesses are owned and run jointly by its members. The organization provides co-op development, land retention, and advocacy to its membership of Black farmers, landowners, and cooperatives.

Today, the Federation continues to advocate for Black-owned farms and businesses across the South. One key piece of its advocacy is land retention. Black farmland ownership peaked in the early 1900s, when nearly a quarter-million farmers owned over 15 million acres of land. Today, Black farmers own around two million acres. In 1985, the Federation merged with the Emergency Land Fund, founded in 1972 to reverse the trend of Black land loss, and added the second half to its official name: the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund.

Dãnia Davy serves as Director of Land Retention and Advocacy at the Federation – a title that encompasses many roles. She supervises the Federation’s legal work, maintains relationships with a network of attorneys across the South, and provides public education and mediation services around the issue of heirs property – the de facto legal process for how land is passed to heirs in the absence of an estate plan. Heirs property, Davy explains, is one of the most notable causes of Black farmland owners losing their land.

On April 30 to May 2, the Berkeley Food Institute, along with American University’s Center for Environment, Community, and Equity and Antiracist Research Policy Center, is teaming up with the Federation to organize Pointing the Farm Bill Toward Racial Justice: A Summit & Briefing. The two-day summit and Congressional Briefing will be a gathering of farmers, scholars, advocates, and policymakers invested in making the 2023 Farm Bill a policy vehicle for advancing racial equity.

In the days leading up to the summit, BFI chatted with Dãnia Davy to discuss her work on heirs property and land retention, the Federation’s policy agenda for the 2023 Farm Bill, and how we can better support self-sustaining rural communities through equitable policies.

BFI: Why are land access and retention such integral components of your work at the Federation?

Dãnia Davy: The Federation’s history is rooted in the issue of Black land loss. In the early 1900s, according to US Census of Agriculture data, African American farmers owned about 15 million acres of farmland. By the 1990s, they owned only about 2 million acres of land. The US became more urbanized and industrialized in general during that period, but there does appear to be a racial component when it comes to the rate at which land is lost. From 1992 to 2002, 94 percent of Black farmers lost part or all of their farmland – three times the rate at which white farmers lost land. Today, Black landowners make up less than one percent of farmland ownership in the country.

There are a variety of reasons for these trends. The first is based on the reality that when the Constitution was drafted, African Americans were legally classified as property. Ever since, legislation and our case law have served to reinforce this idea that African Americans should not own property. Unfortunately, for much of our country’s history, landownership has served as the basis of citizenship, voting rights, and wealth. After the era of enslavement, there were federal policies put in place to increase African Americans’ access to farmland, like the Southern Homestead Act and New Deal-era resettlement projects. But Black landownership was still seen as a threat to the established political and wealth powers at the time, so these federal programs were often stymied by racist practices. Most of the land held by the Freedmen’s Bureau went to white Southerners, for example, and much of the New Deal resettlement efforts were biased toward white land accumulation.

For African Americans who did acquire land, laws and practices were stacked against their keeping it. We’ve seen racial terror as a method for pushing Black people off their land. A lot of their land was also lost to tax foreclosures and discriminatory practices around taxation. The issue of heirs property became a threat to land retention. And there was so much discrimination in credit access that maintaining a farm and being competitive in terms of production was close to impossible.

From 1992 to 2002, 94 percent of Black farmers lost part or all of their farmland – three times the rate at which white farmers lost land. Today, Black landowners make up less than one percent of farmland ownership in the country.

You mention heirs property, which I know is a big focus of your work at the Federation. How would you define heirs property, and how does it threaten land retention?

Heirs property occurs when a landowner passes away without an estate plan. Each state has what’s called intestacy laws. When a landowner passes away intestate, that means they don’t have an estate plan and the state law determines who are their legal heirs and what percentage of the property each heir acquires. Each state has a slightly different approach to intestacy. In North Carolina, where I’m licensed, a surviving spouse will share their inherited interest with any surviving offspring of the decedent, whereas in Alabama, the first $100,000 of estate value is exclusively inherited by the spouse and then the remaining property is shared with the offspring. Each heir then owns a fractionated interest. Say a landowner leaves 40 acres behind to four children. Many people think that each of those four children would then inherit 10 acres, but that’s not the case. Each of those children would inherit one-fourth of 40 acres. If an heir wants to sell, they can’t sell 10 acres of that tract. They can sell only their interest.

This is all part of why the math of who owns what can be so confusing for landowners, and why there is a misunderstanding among heirs of what exactly they own, particularly as the number of legal heirs grows from one generation to the next. There becomes less incentive for an heir with a fractionated interest to participate in the management of a property, which often results in their not paying the correct share of taxes. That’s why we see so much heirs property land loss to tax foreclosure.

There’s another easily exploitable aspect of heirs property. In the example I gave of the four surviving children, say one of them decides to sell their interest to a non-family member, like a land speculator. That speculator can then petition for a partition. Anyone with interest can go to the court and petition for a partition of the land. In a partition in kind, a judge simply divides the property and gives each interest owner a deed. More often, since land value can vary so dramatically from one piece of the same tract to another, the judge would order a partition by sale. The land would be sold, and each interest holder would split the profit. Unfortunately, we often see that the original family owners of the land would not be able to compete with the sale, so, in the end, no one in the family would be able to retain that land.

We’ve seen coordinated efforts between land speculators and developers, wherein the speculator would purchase the interest and then the developer would purchase the property in the partition sale. This is what happened on much of the beachfront property from South Carolina to Florida, which was historically Black owned until speculators bought interest that they then sold to developers who wanted to make resorts. This land is just seen as part of an investment portfolio, which can make it impossibly difficult for heirs property landowners to keep land together, and keep the family together, when there are competing economic priorities that would rather break them apart and cost the family the land. Usually once these families lose the land, they lose it forever.

Are there other disadvantages to being an heirs property owner, and not having a deed, when it comes to running a farm and applying for loans, for example?

Absolutely. That’s a huge challenge that heirs property farmers face. Until recently, the US Department of Agriculture did not recognize heirs property landowners because you need to have your name on the deed to get a farm number, which you need to apply for loans. The USDA is a huge agricultural funder, and it was just uniformly unavailable to heirs property owners. That changed with the 2018 Farm Bill, which authorized the Heirs Property Relending Program to allow heirs to apply for loans to get legal help to clear title, consolidate interest, and make estate plans to that heirs property isn’t created in the next generation.

Of course, the relending program isn’t a silver bullet. A lot of families aren’t in a position where a loan is the best tool for them. But these loans can be necessary if it means helping landowners get clear title to their land. There are estimates that show that about $14 billion of African American wealth is tied up in these tangled title heirs property situations. And that’s a huge drain on our rural community’s wealth base.

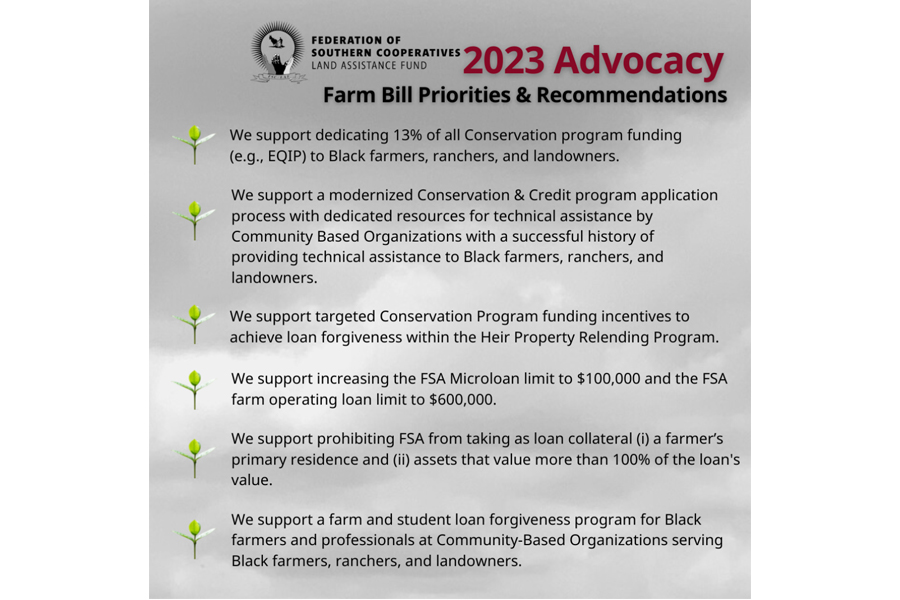

2023 policy priorities from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund.

What are some of the Federation’s policy priorities during this year’s Farm Bill reauthorization?

Last year, we started hosting monthly listening sessions with our members to develop our Farm Bill agenda. The focus of our platform is really on racial equity. Our Farm Bill agenda items prioritize racial equity rather than treat it as an afterthought. The Federation also wants to ensure that conservation plays a huge role in attracting the next generation to farming. A National Young Farmers Coalition survey found that many next-generation farmers are coming into ag to be land stewards. How can we capitalize on that to repopulate the African American farmer population?

One recommendation is that we want to see 13 percent of the Farm Bill Conservation program funding set aside for Black farmers and ranchers. We want to make sure that the funding set-asides match the demographic representation of African Americans in our society and not just in agricultural farmland ownership, because if we keep the set asides to the status quo, all we’re really doing is reinforcing racial inequities.

Another of our priorities addresses heirs’ property in the Conservation program. There’s a USDA program called Debt for Nature in which certain conservation practices would enable farmers to have up to a third of their Farm Service Agency loan forgiven. We would like to see Debt for Nature account for the unique circumstances and challenges of heirs property landowners, such that if a family decides that they want to take out one of these Heirs Property Relending Program loans, they can think of conservation as one of the ways to repay that loan or have part of it forgiven. We’re essentially trying to pair up the Heirs Property Relending Program with the Debt for Nature program. We see this as the best of both worlds, by encouraging and supporting conservation among heirs property landowners as well as helping them make sure that land title issues are resolved.

How did you personally come to this work?

Let me start with: I am a fourth-generation immigrant, and by that, I mean that the last four generations in my family, myself included, have experienced immigration. My father’s family is from Jamaica, and I have some subsistence farmers in my family there. My mother’s family is from Hong Kong. My grandmother had a traditional Chinese arranged marriage in Jamaica. When I came to America, I saw this country as the land of plenty, where everyone had everything they needed. When I learned about racial injustice, I couldn’t understand how this existed in a place as diverse as the United States. I didn’t know then the generational explanation for how systemic racism happens. When I was in law school, I met a farmer named Ben Burkett, who is the Mississippi state coordinator of the Federation. Ben explained to me why Black farmers in particular experience the discrimination and land loss that they do. That conversation changed everything for me. So many things are tied to the land – identity, culture, citizenship. I feel like if we can resolve the racial inequities regarding rural Black communities in the US, I know that we can make all the difference for farming families around the world.