From the Field

Environmental and Food Justice in City Planning: Our SB 1000 Database

In 2016, California passed Senate Bill 1000 to incorporate environmental justice into city and county land use planning. We created a database to assess how this law has advanced policies for food justice.

Throughout United States history, city planning policies have discriminated against low-income communities and communities of color. Industrial land use, transportation, and housing siting decisions have disproportionately exposed these communities to environmental hazards. At the same time, these communities have also had limited access to resources like public open spaces, permanent affordable housing, and nutritious, healthy food. Some people call these communities food deserts. A more appropriate term would be food apartheid — food insecurity is often a result of past decisions made in planning offices.

Even 55 years after redlining was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, communities of color continue to bear the burden of this legacy of discrimination. However, a new state law in California could be an avenue to achieve equitable, justice-oriented land use planning that improves food access and reduces disparities within communities.

On September 24, 2016, California then-Governor Jerry Brown signed into law Senate Bill 1000: The Planning for Healthy Communities Act, which took effect on January 1, 2018. The law requires that cities and counties in California with “disadvantaged communities” incorporate environmental justice into their General Plan, a document that serves as that municipalities development framework. Environmental justice can be integrated as policies throughout the General Plan, or written as a standalone “element,” alongside housing, open space, noise, safety, and other elements typical of a General Plan.

Even 55 years after redlining was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, communities of color continue to bear the burden of this legacy of discrimination. However, a new state law in California could be an avenue to achieve equitable, justice-oriented land use planning that improves food access and reduces disparities within communities.

The goal of SB 1000 is to “reduce the unique or compounded health risks in disadvantaged communities by means that include, but are not limited to, the reduction of pollution exposure, including the improvement of air quality, and the promotion of public facilities, food access, safe and sanitary homes, and physical activity.”

Since May 2022, our research team has undertaken a comprehensive effort to track the implementation of SB 1000 on both the local and county level throughout the state. We also focused specifically on policies that promote food access. We see food justice as an integral component of environmental justice, so we are interested in assessing how General Plans triggered by SB 1000 address issues of food access.

Database Methodology

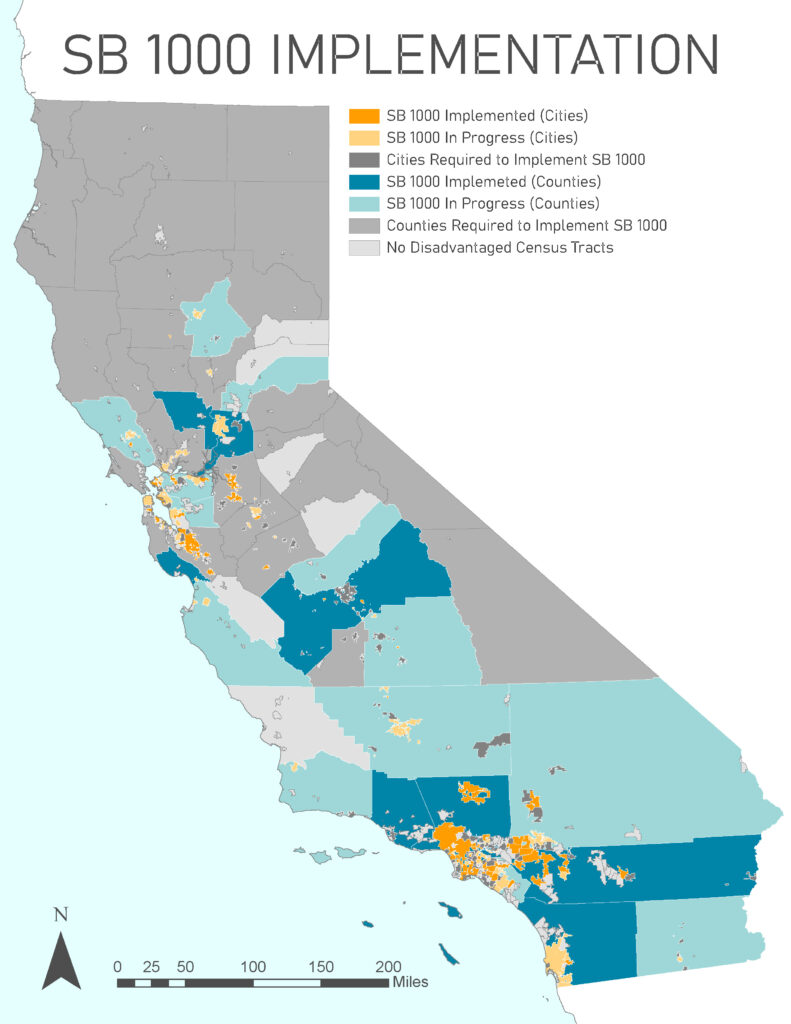

According to the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA), there are 228 cities and 52 counties in the state with “disadvantaged communities” — determined by a pollution indicator tool called CalEnviroScreen and other criteria. Using the mapping software ArcGIS, we overlaid CalEPA’s dataset of disadvantaged communities with their cities and counties to identify all the municipality planning departments responsible for implementing SB 1000. For each of these cities and counties, we located the most recent version of the General Plan. We assessed these General Plans to determine if that city or county is currently in compliance with SB 1000. The law is triggered in these cities and counties when two or more elements of the General Plan are updated concurrently.

Next, we assessed food policies in these General Plans. In each General Plan we located food-related policies by searching for key terms, including SB 1000, Food, Environmental Justice, Agriculture, Farm, Grocery, Nutrition, to identify if that plan had incorporated food policies in accordance with SB 1000.

If food policies were identified, we included the policy in the database along with its corresponding location in the General Plan. We then assessed each policy for how comprehensively it advanced food justice based on six criteria or goals that we devised: food access, nutrition, local food production, edible landscapes, protection of agricultural land, and equity. Not every policy addressed all six goals, but we determined that a “comprehensive food justice policy” addressed at least four of these goals, with equity required as one of the four.

We compiled this research into a database, which we will continue to maintain as cities and counties update their General Plans.

Database Findings

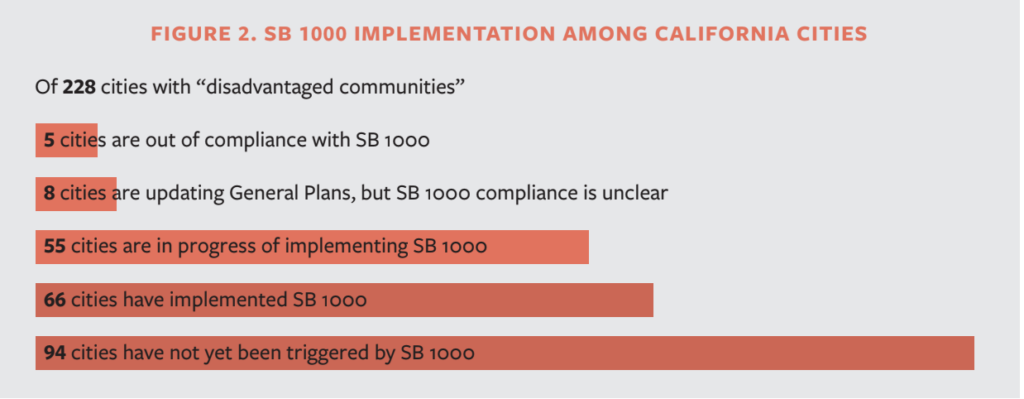

Of the 228 cities with disadvantaged communities, we have found that 215 of them are currently in compliance with SB 1000, either because the law has not yet been triggered, their General Plans are currently being updated in accordance with SB 1000, or they have successfully incorporated environmental justice into their plans. Eight cities are in the process of updating their General Plans but haven’t mentioned SB 1000 or environmental justice in public documents, so their compliance with SB 1000 remains unclear. The final five cities are out of compliance, failing to incorporate environmental justice into their general plans despite updating two or more elements concurrently since 2018. Of the 52 counties with disadvantaged communities, five are currently out of compliance.

While a majority of cities and counties are in compliance with the minimum requirements of SB 1000, the extent to which they comprehensively address environmental and food justice and strategies for implementation vary greatly across cities.

Three cities (Duarte, Bell, and Rosemead) have incorporated environmental justice policies into their general plan, but do not mention food, while an additional 11 cities include food policies that do not adequately address equity. A majority (or all) of the identified policies in these 11 cities address the city as a monolith without considering differences in access and opportunities among communities.

Of the 72 cities and counties that have completed an update of their General Plan in accordance with SB 1000, 40 have written a stand-alone element, while the remaining 32 incorporated environmental justice policies throughout the plan. Additionally, 16 cities had comprehensive food policies in their General Plan pre-SB 1000.

While it is great to see that some cities have already embraced the importance of food justice in creating livable and equitable communities, SB 1000 put legislative weight behind incorporating environmental justice and food justice policies. By counting food policies among the options of environmental justice policies, SB 1000 has helped link environmental justice and food justice, two intertwined yet historically separate social movements.

Examples of Comprehensive Food Policies

The reality is that most cities have not yet implemented SB 1000 since they have not yet been triggered by the law. When that time comes, these city planners can learn from the successes and failures of cities and counties that have already incorporated environmental justice policies. While food priorities may be unique to the municipality, across General Plans, we found that the most comprehensive food policies were actionable, targeted, and specific. That means that they provided concrete steps for implementation, targeted specific communities, and included an impact that could be measurable.

A few examples of these policies are listed below:

- Anaheim: “Support the establishment of farmer’s markets, farm stands, neighborhood markets, mobile health food markets, and other stores that sell healthy food and fresh produce, to expand access to healthy food options throughout the City, with a focus on locations within a walkable distance (i.e., half to a quarter mile away) of EJ Communities.”

- Richmond: “Leverage financial incentives, zoning, technical assistance, and other similar programs to attract grocery store retailers in underserved residential areas of the City. Periodically update information on the location of healthy food sources to track progress on meeting the goals of this element and the Community Health and Wellness Element.”

- San Pablo: “Seek ways to partner with regional Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) as an alternative source of fresh and healthy fruits and vegetables for San Pablo residents, particularly those with limited mobility, limited income, or those furthest from existing grocery stores.”

Conclusion

In conjunction with the database, we have also conducted case studies of Richmond and Gilroy’s environmental justice elements. These cities were chosen because of their comprehensive fulfillment of SB 1000 as well as their targeted, actionable, and measurable policies. We have conducted interviews with planners, policymakers, and community organizations to better understand the policy planning and implementation process.

We have also written a set of recommendations, based on our preliminary research, to improve SB 1000 implementation and its impact on food justice. We have published these in a BFI research report, which you can read more about here.

This research is already making an impact throughout the state. With this database, we have met with the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and the state Attorney General’s Office. With our input, the Attorney General recently published guidelines for local governments on best practices for implementing SB 1000.

Planning and policy play an important role in advancing food justice goals. The Planning for Healthy Communities Act is essential for addressing environmental and food justice in California. By requiring cities and counties to incorporate environmental justice into their General Plans, SB 1000 helps to improve health outcomes in disadvantaged communities and reduce inequity.