Q&A

Liz Carlisle: Regenerative Roots

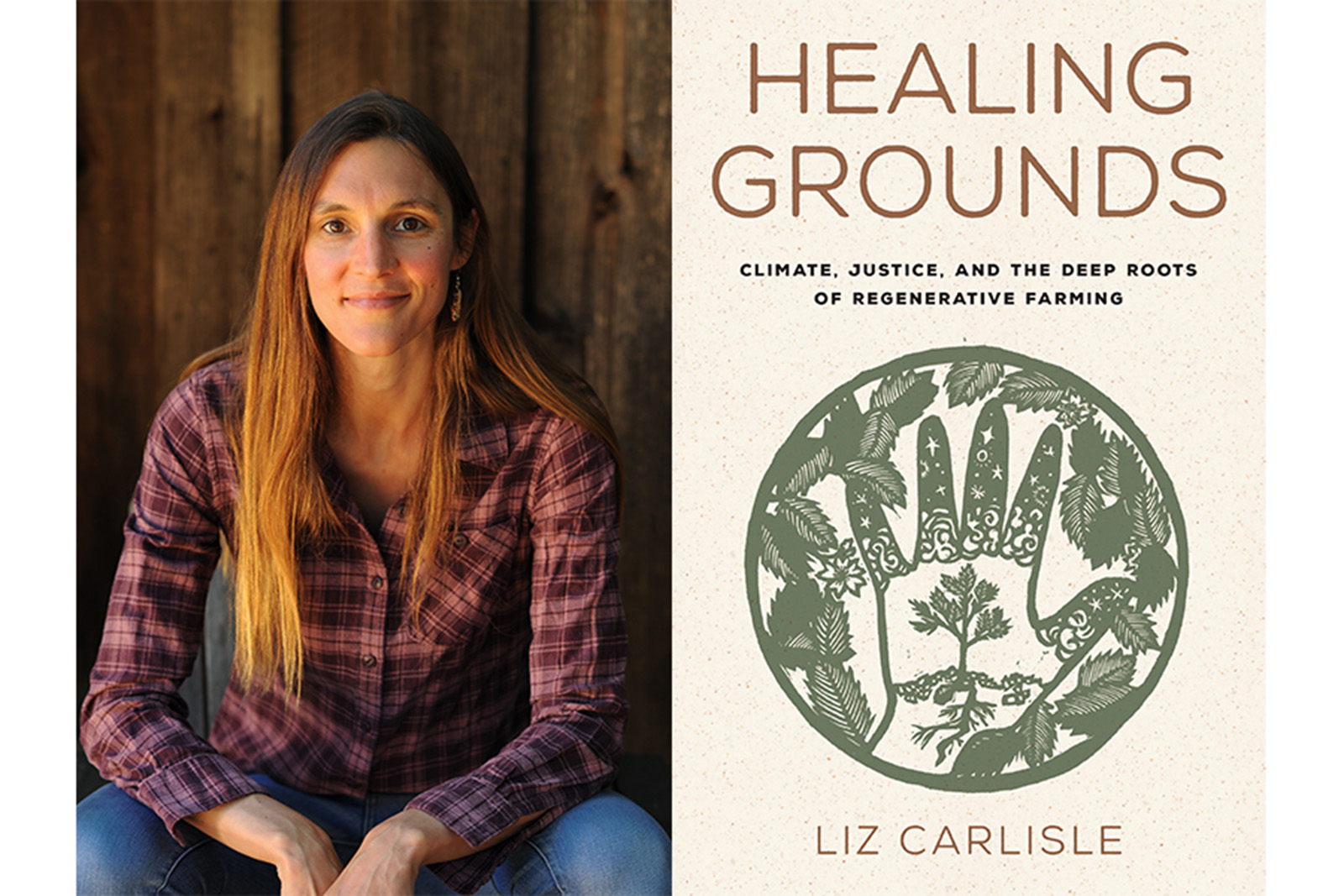

The author of Healing Grounds makes the case for restoring soil through land and racial justice.

Earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released the latest installment of its Sixth Assessment Report. Its message was clear: Mitigating climate change would require major overhauls of the world’s biggest sources of carbon emissions. That includes agriculture, which accounts for roughly a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

For UC Berkeley Geography PhD graduate Liz Carlisle, regenerative agriculture offers a promising solution. In her recent book Healing Grounds: Climate, Justice, and the Deep Roots of Regenerative Farming, Carlisle takes a close look at collection of practices that could restore topsoil that has been overtilled, rebuild biodiversity that has been lost to chemicals and habitat degradation, and lean into the sequestration power of plants. Regenerative agriculture could transform the ag sector from a carbon source to a carbon sink, Carlisle argues — but only if that transformation centers the communities of color that have practiced these land management strategies at the margins of our current US food system.

Based on a decade of research, Healing Grounds explores the history of regenerative agriculture and its potential to be not just a collection of sustainable farm practices but also an avenue for racial and climate justice. “Truly regenerating the web of relationships that support both our food system and our planet is going to take more than compost,” Carlisle writes. “We’re going to have to question the very concept of agriculture, and the bundle of assumptions that travel with the English word farm.”

Now a professor of environmental studies at UC Santa Barbara, Carlisle has a history with the Berkeley Food Institute. She studied with BFI affiliated faculty including Nathan Sayre, Alastair Iles, and Michael Pollan, and she continues to work alongside the researchers at the Center for Diversified Farming Systems on research and policy related to agroecology in California. On a recent visit to Berkeley, Carlisle sat down with BFI to discuss her new book and its contributions to the regenerative ag conversation.

What was the initial question that guided this book, and how did it evolve throughout your research?

I’ve been captivated by the idea that even though farming is associated with a lot of major environmental problems, it can transition to being an environmental solution, particularly when it comes to climate change. Recently, that idea has become more mainstream, at the United Nations and in the media, under this umbrella term “regenerative agriculture.” The authors of the “4 per mille” study for instance say that we could offset 20 to 35 percent of human caused emissions using regenerative agriculture techniques. At the same time, I’ve started seeing this bifurcation in the research community. Other researchers say that regenerative agriculture feels more like greenwashing by Big Food. So I came into this book project wondering, “Is regenerative agriculture a climate solution, really?”

What I found out quickly is that not everybody means the same thing by regenerative agriculture. There were certain regenerative approaches that weren’t changing the underlying extractive logic of agriculture and wouldn’t shift the climate picture. But I also encountered approaches and initiatives rooted in Indigenous communities and communities of color that had been on the frontlines of extractive agriculture for hundreds of years, who deeply understood the root causes of the climate problems with agriculture, and whose vision for regenerative agriculture went deeply enough to actually be a significant climate solution.

Many in the ag sector might see cover cropping, composting, and other regenerative practices as “innovations.” How does seeing these practices as part of ancestral traditions change how we approach regenerative agriculture as a whole?

That’s an important first step, to credit and acknowledge that these practices are not recent inventions. It was interesting for me, progressing through the research for this book, to learn what a powerful climate solution buffalo and prairie restoration led by Indigenous communities can be. Or the practice of agroforestry, which has a long history in Black agrarian movements and the African diaspora. I also learned about these incredible polyculture traditions that date back thousands of years in Mesoamerica, and how immigrants from Central America and Mexico have sustained these traditions on the margins of industrial agriculture. I learned about these incredible nutrient cycling practices with history in Asia that provided the origins of the organic movement in the US. There’s all this regenerative agriculture leadership, all this deep regenerative agricultural knowledge, that’s in the United States, because all these communities are in the United States.

But the next step is to realize that within these communities, these practices are not isolated techniques. They’re embedded within larger philosophies that guide management holistically. These communities show that we need to change the extractive logic behind the current US food system, and we need to shift our relationship with land to be more reciprocal. In the book, I want to present that vision of regenerative agriculture, and suggest that if we’re going to use a word like regeneration, which is a very powerful word, we need to take it to heart. Everything that’s been extracted does need to be repaired. And that involves social processes as well as ecological processes. The two are deeply intertwined.

What are some of the barriers to a large-scale shift to regenerative agriculture within the US food system?

Farmers need capital, technical assistance, access to water, and access to markets. But recent research with Tim Bowles, Alastair Iles, and others at Berkeley has reinforced my sense that land access and secure land tenure is a huge barrier for farmers who wish to build a long-term, reciprocal relationship with land. It’s hard to plant a tree, or even invest in cover crops, if you don’t know you’re going to be able to stay on that land for more than five or ten years.

In the United States, 98 percent of agricultural land is white owned, which is not an accident. We know about the genocide of Indigenous people, and we know what African people suffered through slavery, and we know about centuries of land dispossession through racist policies. How are communities of color supposed to foment a regenerative revolution with just two percent of agriculture land? Land justice and reparations are critical to realizing regenerative agriculture as a climate solution.

Where do you think we, including students and researchers affiliated with BFI, could focus efforts in tackling some of these barriers?

One thing I really appreciate about BFI is that it has a strong commitment to policy at all scales. California is often seen as the laboratory for federal policy and policy in other states and countries. Other states are watching new state policies like the Healthy Soils Initiative, for example, which is providing cost share for farmers who engage in practices that we know have a climate benefit. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act is also important, including the nitty gritty of how that is interpreted and enforced in terms of who actually gets groundwater, because in California, whoever gets the groundwater is who gets to farm. Other states are also watching local policies like the Central Coast’s Ag Order 4.0, which is all about cleaning up nitrogen pollution. Can farmers perhaps get a credit for cover cropping? If we get the details of those policies right in California, those policies will likely get replicated.

We can also engage with the Farm Bill, which could be a vehicle for provisions related to land justice like those in Cory Booker’s Justice for Black Farmers Act. I love the idea of a program that would buy land from retiring farmers and make it available to farmers of color rather than allowing that land to be bought up by institutional investors.

One of the questions of regenerative agriculture is, “How do we heal the ground and make the soil healthy?” But it’s really a multidirectional process. What if we thought of regenerative farming as a practice through which we healed our human relationships, and our relationship with land? One of the clearest physical records of colonialism is land. For a lot of people whose stories I share in this book, colonialism is part of their lived experience, and land reminds them of the scars of colonialism. So in a way, land has to be the place where we repair those colonial processes and find a space of healing.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

To learn more, find Liz Carlisle’s book on her website or at the UC Berkeley library.

Read more about the people and organizations featured in Healing Grounds:

- Aidee Guzman, UC Irvine postdoctoral fellow and UC Berkeley Environmental Science, Policy, and Management PhD graduate

- Nikiko Masumoto, farmer at Masumoto Family Farm

- Stephanie Morningstar, executive director of the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust

- Mai Nguyen and Neil Thapar, co-directors of Minnow

- Latrice Tatsey, graduate student in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences at Montana State University

- Olivia Watkins, farmer at Oliver’s Agroforest